Are Stocks More Overvalued than they were in 2000? A look at the S&P 500 25-Year Chart

Barron’s — We all knew that Donald Trump was the real estate promoter nonpareil. But who knew what a great stock salesman he was?

The day after his speech to a joint session of Congress on Tuesday evening, the stock market surged. The rally was paced by a boom in buying of exchange-traded funds, especially the biggest of them all, the SPDR S&P 500 (ticker: SPY). Spyders, as the ETF is called by its fans, attracted over $8 billion on Wednesday alone. That was the biggest daily influx into the world’s No. 1 ETF since December 2014, according to strategists at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, and accounted for the lion’s share of inflows into equity mutual funds of all stripes, which totaled $9.8 billion in the week ended on Wednesday.

The ever-effacing chief executive took credit for the stock market’s advance, tweeting of $3.2 trillion in gains in U.S. share values since the election. As for Wednesday’s 300-plus-point jump in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, observers from all vantage points credited Trump’s performance the prior evening, which featured a far more tempered tone, if little new of substance. In that, it recalled the moonshot in stock futures in the wee hours of election night, in reaction to his conciliatory victory speech.

Whatever the president’s role in the stock rally, the advance has been powerful enough to attract the attention of the nonfinancial media. Following the stampede into Spyders, the stock market merited page-one coverage in Thursday’s New York Times (albeit down near the bottom, “below the fold,” for those who still prefer to hold paper). That, in turn, attracted the attention of PBS Newshour, which dutifully debriefed the Timesman (the nomenclature of a less-enlightened era) for the benefit of its viewers, who tend to be less knowledgeable about investments than about imported British soap operas.

Not that HGTV is about to trot out a new series called Flip This Stock, but Dow 20,000 and 21,000 have gotten noticed. And a hot initial public offering for Snap (SNAP) attracted a crowd to the New York Stock Exchange, as in the good old days of the tech bubble. And as in those days, the valuation was over the moon, as the story on Snap notes.

Even before Wednesday’s surge in prices and coverage, so-called retail investors had been driving the stock rally, according to Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, who tracks fund flows with an eagle eye for JPMorgan. If anything, he says, institutions this year have kept their equity exposures unchanged or have pared them, according to the bank’s indirect tracking of their stances. Individuals, in contrast, have been buyers of ETFs and driving the rally, he says.

And it seems that online brokers are scrambling for bigger pieces of the action by waging a price war that escalated last week, with Fidelity cutting its commission to $4.95, leapfrogging Charles Schwab ’s (SCHW) previous drop to $6.95. Schwab matched that cut, while rivals TD Ameritrade (AMTD) and E*Trade Financial (ETFC) went to $6.95. This online broker mania also recalls the halcyon dot-com days. All we need is a revival of the old ad with the young guy exhorting his elder office mate to “light this candle” and trade on his dial-up connection. (For more on the online-broker scrum, see the ETF column.)

Stocks aren’t cocktail-party chatter yet, avers Doug Ramsey, chief investment officer at Leuthold Group. If anything, the bull market that’s about to mark its eighth birthday has been puzzling, in that it’s gone this far without big public participation until recently. And notwithstanding the media notice in recent days, he adds, the Standard & Poor 500’s return of 12% in 2016 and its 6% gain this year isn’t about to get folks bragging about their index funds.

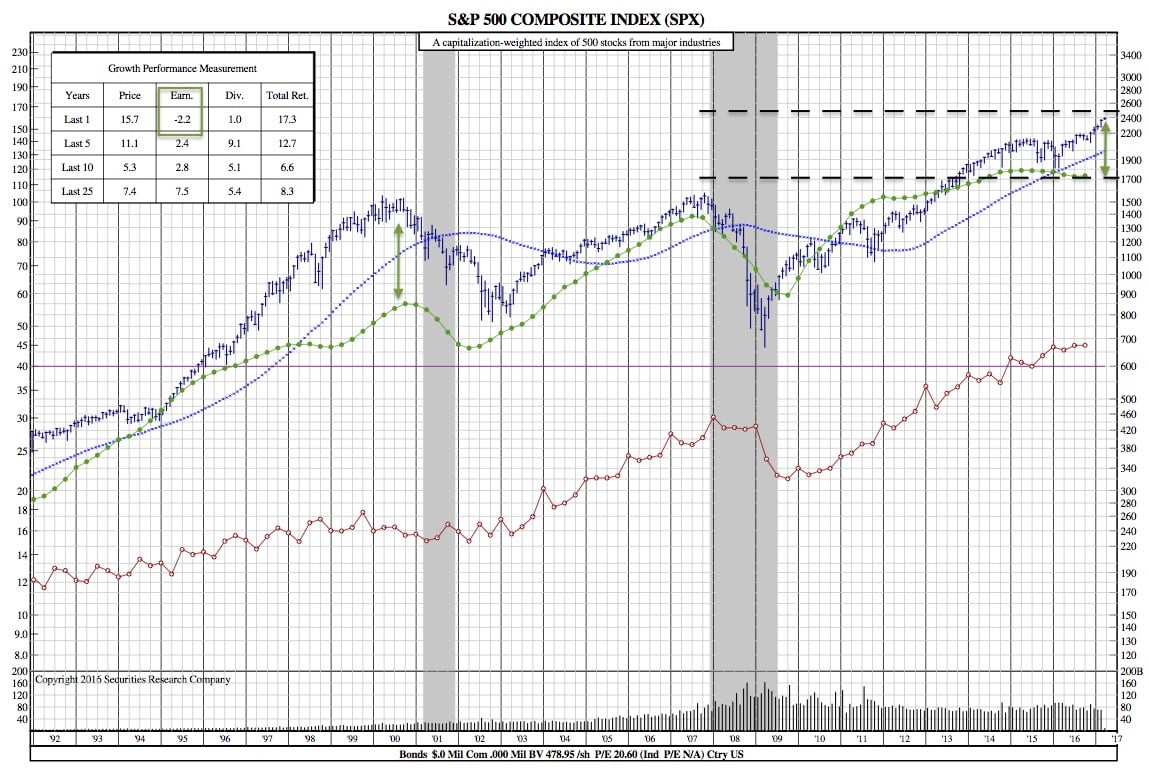

SPX 25-Year Chart:

Anyway, public participation isn’t necessary for the bull to continue, he continues. The 1976-80 advance saw no inflows into equity funds until the very top. And during the bull market of the aughts, there wasn’t a lot of public buying until 2006-07, close to the market top. The mania then, Ramsey muses, was house-flipping.

Sentiment is ebullient, to say the least. Investors Intelligence’s polling shows bulls at 63.1% of respondents, the highest reading since 1987. That makes 14 weeks in which the number has been over 55%—what II dubs the “danger zone.” Bears were down to 16.5%, the lowest figure since July 2015. That put the bull-bear spread at 46.6 percentage points, the highest for the current market cycle. (Some 20.4% were looking for a correction, around the recent level.) Talk is cheap, but for those plunking down dough in the options market, JPMorgan also found a high “skew” of bullish calls over bearish puts in out-of-the-money contracts.

The market’s advance looks solid from a technical standpoint, with small- and mid-cap stocks, transportation shares, and overall market breadth looking positive, Ramsey adds. Even utility stocks, which were thought to be so last year with the reflation trade now in vogue, are only a few percentage points below their high.

But Ramsey worries about stock valuations broadly, based not on a single metric, but rather on an array of measures, including price/earnings ratios, normalized P/Es, and price-to-sales ratios, to name a few. Viewed that way, he says, stocks haven’t been as overvalued since the dot-com peak of March 2000. But that doesn’t preclude the S&P 500 from reaching 2500 or 2600 before valuations get totally stretched, he adds.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch strategists have dubbed 2500 on the S&P 500 as their target for the “Icarus trade” that also sends bond yields, the dollar, and oil higher before their wings melt.

Ramsey recalls the observation of the legendary market watcher Richard Russell, who warned that the market tries to get as many bulls to crowd into an elevator before it heads lower. The doors haven’t closed yet. But to a claustrophobe, the car is beginning to feel a bit snug.

Whatever the motivation for the stock market’s ascent, its unequivocal implication has been to make an increase in short-term interest rates a near certainty at the next meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, on March 14-15.

Federal-funds futures contracts say there’s a 94% probability that the central bank will lift its key interest rate target by 25 basis points (one-quarter of a percentage point), to 0.75% to 1% at the March confab, according to Bloomberg. That’s more than double the chance the market saw just a couple of weeks ago, when this column’s online edition warned that an increase was likely (“The Ides of March Could Deliver a Fed Rate Hike,” Feb. 16).

At that time, it was noted that the Federal Reserve essentially had met its two official objectives in terms of full employment and inflation. As such, it was hard to see what excuse the central bankers could come up with for not raising rates.

Last week brought a parade of Fed speakers, all on-message that conditions were in place for the first of the three 25-basis-point increases the FOMC implicitly predicted for 2017 at its December meeting. And in this case, it ain’t over until the petite gray lady sings, a condition that Chair Janet Yellen satisfied with an address on Friday afternoon. In it, she said that “a further adjustment” in the fed-funds rate would be appropriate at the coming meeting.

“The economy has essentially met the employment portion of our mandate, and inflation is moving closer to our 2% objective. This outcome suggests that our goal-focused, outlook-dependent approach to scaling back accommodation over the past couple of years has served the U.S. economy well,” Yellen said. In other words, mission accomplished.

That might have been said a year ago, when the FOMC was penciling in four 25-basis-point rate hikes for 2016. Of course, there ended up being only a single move, and not until December. Early in the year, concerns about China and the oil-led commodity slide that battered the capital markets stayed the Fed’s hand. Then came the Brexit vote near midyear and then uncertainty ahead of the U.S. elections.

Even having fulfilled its dual mandates, some wonder why the Fed is moving now. Conspiracy theorists suspect that the Yellen-led central bank is intent on ruining the Trump economic agenda by raising rates. Others are puzzled why the Fed should tighten policy if the moderate tenor of economic data hasn’t changed.

Barclays economists answer the latter argument regarding a likely rate increase: “As U.S. data have been solid, but not exceptional, we believe the shift is driven by the improvement in financial conditions—specifically the rally in equity markets—since the election, a rally that is evident to a greater or lesser degree in most major markets.”

Only a shockingly weak employment report for February would deter the Fed from lifting its fed-funds target at the March meeting. The consensus of economists’ forecasts calls for an 185,000 increase in nonfarm payrolls, in line with the recent monthly average, and a downtick of one-tenth of a percentage point in the jobless rate, to 4.7%.

Also closely watched will be the trend in average hourly earnings, which may be up only 0.2% for the month, a continuation of the tepid pace of wage gains.

Fed-funds futures now are in sync with the FOMC’s dot plot of rate forecasts. Odds are a bit better than 50-50 for a 1.25% to 1.5% target by year end.

With monetary policy becoming less accommodative, Barclays economists also think the timetable for the Trump agenda is likely to be delayed. The peak stimulative impact won’t arrive until the third quarter of 2018, they reckon. That would come just before the midterm elections, convenient politically, but perhaps later than the markets now anticipate.